Equilibrium/Sustainability — WHO tells Ukraine to destroy pathogens

Today is Friday. Welcome to Equilibrium, a newsletter that tracks the growing global battle over the future of sustainability. Subscribe here: digital-stage.thehill.com/newsletter-signup.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for Ukraine to destroy all high-threat pathogens in the country’s laboratories to preempt any leakages of toxins that could cause disease spread, Reuters reported.

“WHO has strongly recommended to the Ministry of Health in Ukraine and other responsible bodies to destroy high-threat pathogens to prevent any potential spills,” the organization told Reuters in a statement.

Russia’s incursion into Ukraine and its bombardment of cities has increased the risk that disease-causing pathogens could escape such laboratories, if any of these buildings sustain damage, Reuters reported, citing biosecurity experts.

While the WHO did not provide any specifics about the types of toxins housed in Ukraine’s laboratories, the organization made no reference to biological weapons — despite longstanding Russian claims that the U.S. operates a biowarfare facility in Ukraine, according to Reuters.

Today we’ll examine spills of toxic chemicals over the past 30 years. Then we’ll break down where Russia’s oil went before the Ukraine invasion, which helps explain the geopolitics of today.

For Equilibrium, we are Saul Elbein and Sharon Udasin. Please send tips or comments to Saul at selbein@digital-stage.thehill.com or Sharon at sudasin@digital-stage.thehill.com. Follow us on Twitter: @saul_elbein and @sharonudasin.

Let’s get to it.

Nearly 900 spills of foam over 30 years

Nearly 900 spills of firefighting foam containing toxic “forever chemicals” have occurred across the country since 1990, new data published by the Environmental Protection Agency has revealed.

The dataset, provided to the EPA by the U.S. Coast Guard’s National Response Center, showed that there have been 897 spills or usage reports of aqueous form filming foam, a material used to fight jet fuel fires on military bases and civilian airports. Firefighting foam is one of the most common sources of so-called forever chemicals, the umbrella group for thousands of compounds known as per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

A refresher on PFAS: Linked to a variety of illnesses, like thyroid cancer, testicular cancer and thyroid disease, PFAS have a propensity to linger in the human body and in the environment.

While they are most known for their presence in firefighting foam and industrial discharge, they are also key ingredients in a variety of household products, such as nonstick pans, waterproof apparel and cosmetics.

DOD, federal sites among the most frequent offenders: Many of the sites that had the biggest firefighting foam releases in the National Response Center database were Department of Defense and other federal facilities, while others were commercial harbors and civilian firefighting events, according to an analysis of the dataset conducted by the Environmental Working Group.

The Department of Defense was responsible for six of the 10 largest spills listed in the dataset, according to the Environmental Working Group.

Where and when were the worst spills? The largest discharge of firefighting foam to end up in a waterway was a 805,000-gallon event at Melbourne Orlando International Airport in Florida in 1995, when a hanger fire prompted the firefighting foam system to release the foam, the analysis found.

The next biggest spill to leech into a waterway, per the data, was a 140,000-gallon spill in Guntersville, Ala., in 1998, when a wall collapsed during a fire alarm test and discharged firefighting foam into Lake Gunters. Following this event was a 100,0000-gallon spill during a power outage in San Antonio, Texas, in 1992.

“It is unclear whether surrounding community water supplies were contaminated by PFAS from the spills or use of the aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, that contained the chemicals,” a statement from the group said.

A COMPLICATED HISTORY OF FIREFIGHTING FOAM USE

The Air Force first started using firefighting foam in 1970 as part of firefighting and crash response exercises and emergency response efforts, the Defense Department branch previously told The Hill. Firefighting foam is “mission critical because it is the most efficient extinguishing method for petroleum-based fires,” and the Federal Aviation Administration also mandates its use at both military and civilian airport fire stations, the Air Force stated.

In recent year, the Air Force restricted the use of firefighting foam to emergencies only.

While the EPA posted the data on its website, the agency did so with the caveat that the National Response Center “serves as an emergency call center that fields initial reports for pollution and railroad incidents,” and that the data “has not been validated or investigated by a federal/state response agency.”

A deluge of data: The records on firefighting foam spills were published alongside a variety of other Excel files as part of the EPA’s PFAS National Datasets. Among the other datasets:

- Ambient environmental samples for PFAS

- Drinking water tests

- PFAS manufacture and imports

- PFAS detections at hazardous waste sites

- Clean Water Act discharge monitoring

- Industrial facilities that may be handling PFAS.

The national organization Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility responded to the release of the data on Thursday, noting that the publication only occurred following three years’ worth of requests from the group.

Last words: “We are glad this information was finally released,” Tim Whitehouse, executive director of [Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility], said in a statement. “It will provide regulators and researchers with important information about the growing crises of PFAS pollution in the United States.”

BE IN THE KNOW

We’ve got you covered morning, noon, and night! Sign up now for The Hill’s new Evening Report.

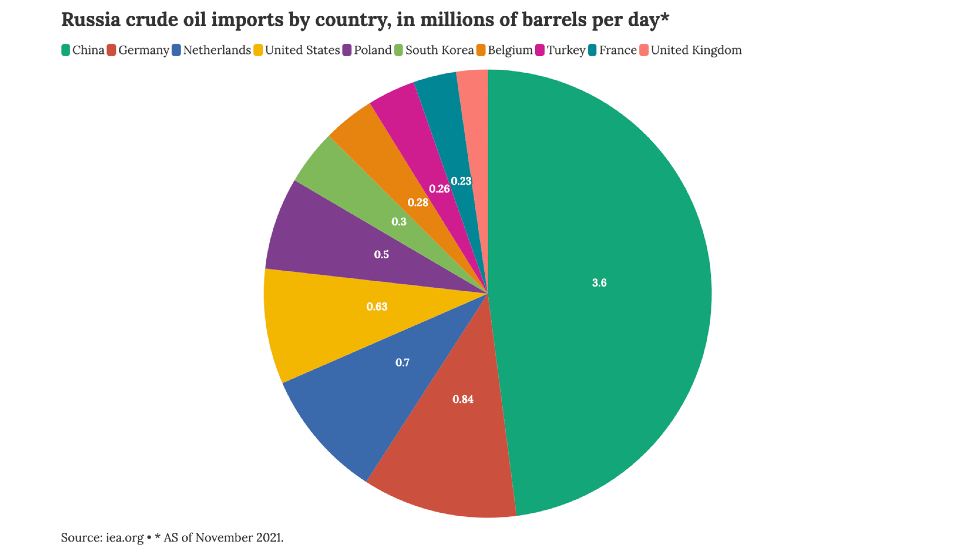

Where Russia’s oil went before the war

As governments around the world start to turn off the tap on Russian oil, a closer look at where precisely that oil was going before Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine can provide some insight on what might be in store for the oil landscape’s future.

The vast majority of Russia’s oil exports were being purchased by Europe and China, which together accounted for 90 percent of the country’s total exports.

That’s made it tougher for Europe to enact similar bans as the U.S. has on Russian imports, and Russia’s diverse range of petro-customers helps lessen the economic hit to Moscow from the Biden administration’s decision this week to cut off Russian oil.

First steps: Even after this week’s U.S. embargo of Russian oil, Russia remains the world’s largest exporter of oil to global markets and, behind Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-largest exporter of crude oil, exporting about 2.85 million barrels per day by sea lanes and pipelines, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Where does that go? The largest single importer is China, which in November 2021 was importing about 3.6 million barrels per day from Russia, split evenly between ships and pipelines.

But Europe is by far Russia’s largest collective buyer for oil and refined petroleum products. As a bloc, the E.U states purchase more petroleum products than are used in Russia itself.

In 2021, Europe used about 42 percent of the petro-state’s total oil production, followed by Russia itself at 30 percent and China at 14 percent.

Let’s break that down further: In November 2021 — four months before the February invasion — these were the top 10 importers of Russian oil by volume:

- China 3.6 million barrels per day

- Germany 835,000 barrels per day

- Netherlands: 700,000 barrels per day

- U.S. 625,000 barrels per day

- Poland: 500,000 barrels per day.

- Korea: 300,000 barrels per day

- Belgium: 280,000 barrels per day

- Turkey: 258,000 barrels per day

- France: 230,000 barrels per day

- UK: 170,000 barrels per day

HOW DOES THAT TRANSLATE TO DEPENDENCE?

That’s a more complicated question, because some of the countries most dependent on Russian oil — like Lithuania — don’t import very much of it.

Many are heavily reliant: Lithuania gets 83 percent of its oil imports from Russia, followed by Finland (80 percent), Slovakia (74 percent), Poland (58 percent), Hungary (43 percent) and Estonia (34 percent).

Germany imports about 30 percent of its oil and petroleum products from Russia, joined by Norway (25 percent), Belgium (23 percent), Turkey (21 percent), Denmark (15 percent) and Spain (11 percent).

How does that compare to the U.S.? Europe as a whole imports about seven times as much oil from Russia than the U.S. does.

But these comparisons understate the dependence: Unlike the U.S., Europe doesn’t have much oil production of its own to speak of, and to diversify the supplies for its cars.

The one exception to that rule is Norway, which is the world’s 13th largest producer. While a quarter of its oil imports came from Russia, the 45,000 barrels it imported from Russia every day in 2021 paled in comparison to the more than 2 million barrels it produced itself.

What about other fossil fuels? Russia is a major producer, consumer and exporter of not just oil but also of coal and natural gas, and of the various refined products made from these resources. Russia’s fossil fuel industry produced the energy equivalent of 11 billion barrels of oil in 2019, according to the IEA.

Takeaway: Since most of the oil that Europe imports from Russia goes to transportation and heating buildings, if European governments want to reduce their dependence on Russian energy, then their best option is to prioritize the electrification of transport and heating sectors.

VIRTUAL EVENT ANNOUNCEMENT

Virtual Event Invitation—A Connected & Sustainable Society—Wednesday, March 16 at 1:00 PM ET/10:00 AM PT

Leaps in digitalization refine the way we live, learn and work. At the center of these transformations are high-powered networks that make connectivity and data optimization possible. Join The Hill’s Steve Clemons for conversations with Sen. Deb Fischer (R-Neb.), Rep. Robin Kelly (D-Ill.), Rep. Grace Meng (D-N.Y.) and more on the role of networks in creating a more sustainable, equitable and livable tomorrow. RSVP here.

Follow-up Friday

Philadelphia council member pushes bill to eliminate lead in schools

- Childhood exposure to leaded gasoline reduced IQ scores for half of Americans alive today. On Thursday, Philadelphia City Council member Helen Gym proposed a bill that would force Philadelphia schools to expedite the installation of water filtration systems to eliminate lead, WHYY reported. A recent report from local green groups showed that nearly all Philly schools tested had at least one outlet — like a fountain or sink — that contained lead, according to WHYY.

Southern California still awaiting plenty of tourists’ cars

- Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-Calif.) proposed offering rebates to California families pinched by rising gas prices. But despite the rising prices that has many drivers restricting their mileage, the San Diego tourism industry is still expecting a big year, according to 10News.

Supply chain worries cut EV startups production in half

- Sanctions to Russia’s metal industry might constrict the supply of nickel needed by the American electric vehicle industry. That could drive up prices, making it tougher for customers to find new electric cars. Pickup startup Rivian has already halved its production forecast for 2022, citing supply chain worries, Reuters reported.

Be sure to visit The Hill’s website this weekend, to read about how a Ukrainian dam has played a key role in tensions with Russia — and why one of Moscow’s first strategic moves after invading the country was to blow up this controversial facility.

Please visit The Hill’s sustainability section online for the web version of this newsletter and more stories. We’ll see you on Monday.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts