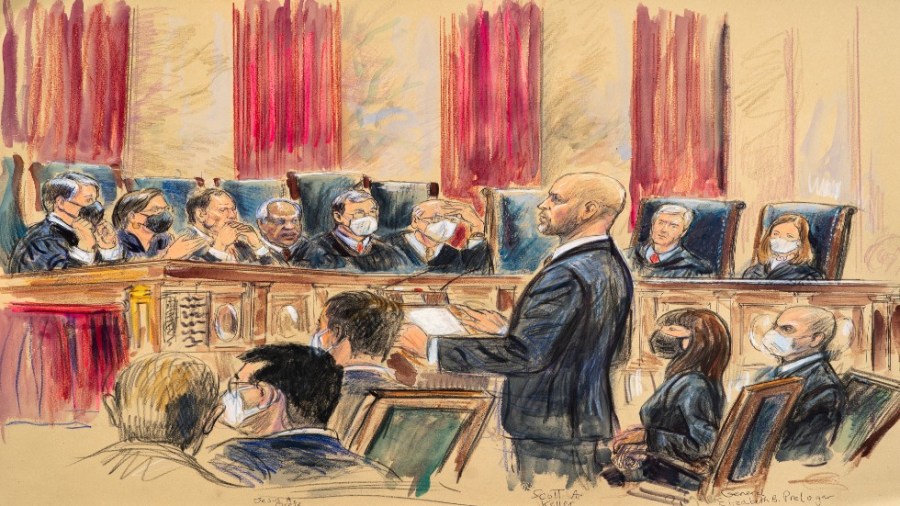

On Friday, the Supreme Court heard arguments for an emergency stay of President Biden’s rule protecting workers from COVID-19.

Just a few years ago, no good lawyer would have wasted his client’s money asking the Supreme Court to review an emergency stay, because such stays are disfavored and the court almost never reviewed requests for preliminary orders. The court also recently issued rulings addressing preliminary motions in abortion cases and decided to review Clean Air Act regulation of power plants before the Biden administration even issued emission standards.

Traditionally, the court almost always reviewed final ruling appellate decisions. That custom enabled the court to consider important legal questions with the benefit of the insights of lower court judges, a full record and ample time for reflection. In the COVID case, the court seems to be flirting with declining to allow President Biden to use express legal authority to protect health on the ground that Congress should make case-specific decisions. That’s a radical constitutional idea demanding slow and careful deliberation unavailable in a case based on a preliminary order.

Traditionally, the Supreme Court has been an appellate court, but increasingly it acts like a trial court in deciding motions, and not a very fair one.

Since around 2016, however, the court has increasingly used its “shadow docket” to issue important early rulings without briefing or oral argument and often without any explanation. While the COVID and Clean Air Act cases will involve briefings and oral arguments, they share with the shadow docket the problem of violating norms limiting hasty Supreme Court intervention in disputes.

The court’s increasingly frequent premature rulings often shielded President Trump from inconvenient orders and considerably and quickly advanced the Republican Party’s interests. The court almost never follows the rules governing wise adjudication of preliminary orders, which focus primarily on fairness to the parties. Under that standard, the court would never consider reversing a denial of an emergency stay of a rule designed to save lives, like the COVID rule. Instead, it bases these preliminary rulings on its quickie take on where the merits might end up after the court has time to completely consider them.

In this way, its hasty interventions create the impression that the court is not carefully and objectively considering a legal issue in light of all sides’ arguments and a specific record, but instead, trying to quickly achieve results it considers desirable for political reasons.

If the Supreme Court ever acted like an umpire calling ball and strikes, it certainly has ended that tradition in the last few years. Increasingly, it reaches down to the minor leagues to select a pitcher to throw it a pitch it would like to hit.

For many decades, the legal system relied on a tradition of judicial restraint to ensure that the court performed its properly limited role in a democracy. The Supreme Court selects its own cases and writes its own rules. Only self-restraint kept the court from actively seeking out issues that it would like to weigh in on and quickly stopping fair preliminary lower court actions or heading off pending executive branch decisions that justices might find ideologically uncongenial.

With the tradition of judicial self-restraint as to timing now abandoned, it’s time to consider legislative restraints. Biden should ask his Supreme Court Commission to consider imposing hard limits on what cases the court may hear early. So far, the commission has not advanced court reform, because Biden has not asked it to make recommendations.

It makes sense not to ask for recommendations on issues like rebalancing the court, the issue that led to the commission’s creation. After all, sensible judgment about whether to add justices to the court depends upon political judgment about whether the need to improve the court’s ideological balance outweighs the long-term risk of undermining judicial independence.

But legal scholars generally agree that the court has been overreaching in its eagerness to decide politically important issues early. That consensus might lead to some agreement on what reforms are appropriate, which may even translate into proposals that, sooner or later, could pass the Congress and limit the damage the court inflicts on itself and the society it is supposed to serve.

In short, there may be some relatively low-hanging fruit here, which the Biden administration should pluck.

David M. Driesen is a professor at Syracuse University College of Law.