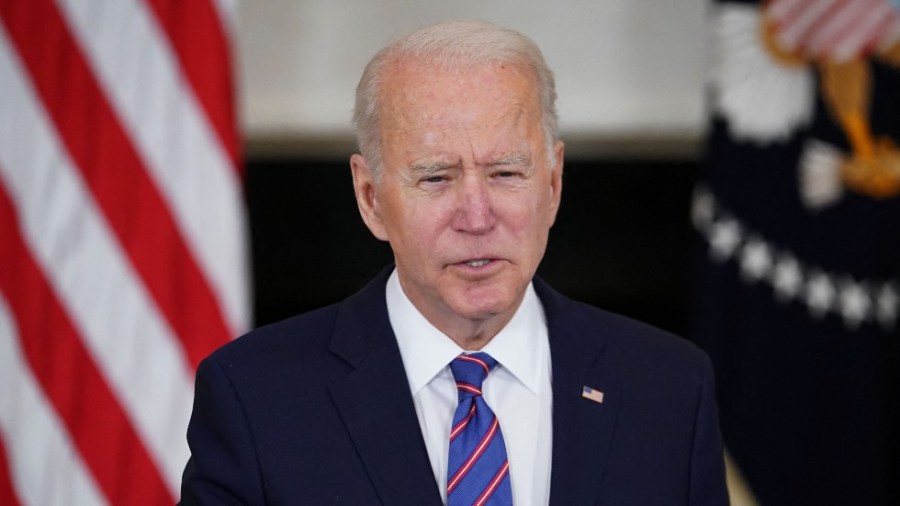

When Joe Biden was elected president, investors were divided about whether he would govern as a centrist or as a progressive. By now, the answer seems clear: Biden is seeking the largest expansion in the federal government’s involvement in the economy since Lyndon Baines Johnson’s “Great Society.”

The Biden administration is moving in phases to tackle problems that it believes are holding back the American economy. The first phase – the “American Rescue Plan” – contained $1.9 trillion in relief to lower-and-middle income households until COVID-19 vaccines allow the economy to re-open fully. This support was in addition to the $900 billion package enacted at the end of 2020.

Subsequently, President Biden this week unveiled the next phase of his plan — the “American Jobs Plan.” It calls for federal spending of $2.3 trillion this decade to build out public infrastructure, green energy and other projects that are intended to create millions of jobs and to enhance America’s competitiveness. It is expected to be followed next month by a program to improve “human infrastructure” via spending on community colleges, universal pre-K and a national paid leave program.

The combined tally of these two proposals is estimated to be $3 trillion to $4 trillion over this decade. With the federal budget deficit already at a post-war record of 14 percent of GDP, the Biden administration is looking for ways to finance these programs.

The proposal Biden put forth this week to finance the public infrastructure program would raise the marginal corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent, mandate a 15 percent minimum tax on book income and impose additional taxes on overseas earnings of U.S. multinationals. If enacted, they would offset about two thirds of the increase in federal spending over the next eight years and more than cover the costs over a 15-year horizon.

The main issue for investors is whether these proposals will be enacted. The COVID relief bill was passed strictly along partisan lines, with no Republicans supporting it. The challenge for the Democratic leadership will be to see if they can maintain support of all the Democrats in the Senate and most of those in the House.

One thing the Biden administration has going for it is that public support for public spending has increased since the pandemic struck. Also, there is widespread recognition that spending to maintain roads, bridges and waterways, as well as to build out broadband, is inadequate. Indeed, the American Society of Civil Engineers assigned a “D+” rating in assessing the quality of U.S. infrastructure in 2017 after President Trump assumed office. It has since been upgraded to “C-.”

Nonetheless, the efforts of both the Obama administration and the Trump administration to increase spending on public infrastructure failed to produce tangible results. This begs the question: What makes public infrastructure spending so difficult if it is so popular?

According to DJ Gribbin, who served in the Trump administration, one of the mistakes it made was to assume the federal government is the primary owner of the country’s infrastructure. In fact, it owns only about 6 percent of the nation’s transport and water infrastructure, and its main role is to supply grants to states and municipalities and to regulate environmental and safety rules.

Gribbin contends that one of the challenges for the Biden administration will be to keep its plan tangible, “but not get lost in the minutiae of specific projects and fail to reform the federal role in infrastructure, which still largely dates back to the 1950s.”

Weighing this admonition, how does Biden’s infrastructure plan stack up? The most glaring problem is that it is overly ambitious and not targeted at meeting the greatest needs.

For example, the bill can be broken down into four major categories: (i) transportation; (ii) buildings and utilities; (iii) jobs and innovation; and (iv) in-home care.

Of these, the transport component comes closest to what most people think of as public infrastructure and is estimated to cost $620 billion, or one quarter of the total. It would modernize 20,000 miles of highways and roads, repair 10,000 bridges and build out a network of 500,000 electric vehicle chargers by 2030. Another $200 billion would be allocated for high-speed broadband, electric grid and clean energy.

By comparison, the other components have less to do with what is normally thought of as public infrastructure. Yet, their costs are close to 60 percent the total. The plans for buildings and utilities call for more than $200 billion in tax credits and grants to improve and build affordable housing. Another $500 billion would be used to invest in manufacturing, worker training and R&D, while $400 billion would be used to expand access to caregiving and to improve pay and benefits for caregivers.

In the end, my advice to investors is not to over-react to the current proposal: It will be difficult to pass such a sweeping program when the economy is already poised for a powerful expansion. While the Biden administration pulled off an impressive victory with the COVID relief bill, it will need to redraft a more pared-down version of the infra-structure bill to have a better chance of passage.

Nicholas Sargen, Ph.D., is an economic consultant and is affiliated with the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business. He is the author of “Investing in the Trump Era; How Economic Policies Impact Financial Markets.”