EU celebrates an end to Greek aid as an Italian storm looms

Monday marked the day that Greece finally emerged from eight years of tutelage under an International Monetary Fund (IMF)-European Union economic adjustment program.

This is giving rise to celebrations in some official quarters in Europe that finally the euro crisis is over. As an example, Klaus Regling, the managing director of the European Stability Mechanism, says that he will be drinking a glass of ouzo to celebrate this important Greek milestone.

{mosads}Evidently, Regling is not paying attention to two factors. The first is the extraordinarily sorry state in which Greece has emerged from its IMF-EU program as well as the country’s still very gloomy economic prospects.

The second is a brewing Italian financial and economic crisis that could have very much more serious consequences for the euro than did the earlier Greek economic crisis.

Had Regling been paying attention to those two factors, he might have been drinking ouzo not so much to celebrate but as to drown his sorrows.

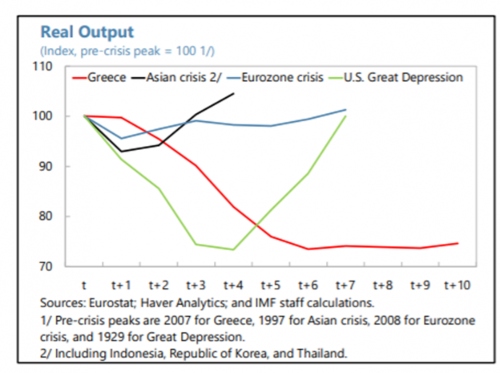

A recently published IMF chart properly depicts the sorry state of the Greek economy. That chart shows that Greece’s economic depression has been, in at least one important respect very much worse than the U.S. Great Depression of the 1930s.

As in the Great Depression, Greece’s output dropped by some 25 percent from its pre-2010 economic peak. However, unlike the Great Depression, which touched bottom some four years after it started and regained its pre-crisis level some four years later, the Greek economy is yet to turn decisively upward, and it is still some 25 percent below its pre-crisis level.

In addition, over 20 percent of the Greek population remains unemployed despite the fact that more than 400,000 of its more economically active citizens chose to leave Greece in search of better work opportunities abroad.

It is also hardly a cause for celebration that the country remains saddled with a debt burden that the IMF acknowledges is not sustainable or that it has emerged from the crisis with very fragmented domestic politics.

Those politics have thwarted Greece from adopting those economic reforms that might have placed it on a faster economic growth path than it currently finds itself. They also reduce the prospect that the country will have any more success in reforming its economy going forward than it has had to date.

A second and more important reason why it would be premature to think that the euro crisis is over is that storm clouds are gathering over the Italian economy.

This would appear to be all the more the case considering that the Italian economy is some 10 times the size of the Greek economy and, after the U.S. and Japan, it is the world’s third-largest sovereign debt market.

If the Greek economic crisis shook the eurozone’s economy to its core, one has to shudder to think what would happen to Europe if Italy were indeed to experience a full-blown economic crisis.

A primary reason to think that the Italian economy is headed for real trouble in the period immediately ahead is that it is more vulnerable than ever to a change in the global liquidity environment.

At a time that the Federal Reserve is already raising interest rates and that the European Central Bank is due to end its bond-buying program by year-end, Italy’s public-sector debt has risen to over 130 percent of GDP, making Italy, after Greece, the eurozone’s most indebted economy.

At the same time, the Italian banks’ balance sheets are saddled with worryingly high levels of non-performing loans as well as with uncomfortably high levels of Italian government debt.

Further clouding the Italian economic outlook is the fact that following last March’s elections, Italy now has a populist coalition government that is not committed to budget discipline and that is intent on rolling back the economic reforms of the previous Italian government.

If the Italian economy was unable to grow under a reform-minded government during a period of a favorable global economic environment, one has to ask why it should be expected to grow in a more challenging global environment and with a government whose economic policies are unlikely to be supported by the markets.

Without economic growth, how is Italy supposed to deal with its public debt mountain in a challenging global liquidity environment?

All of this suggests that now is hardly the time for European policymaker complacency. Instead of celebrating the end of the IMF-EU Greek bailout program, now would seem to be the time for European policymakers to be planning how they will be addressing the next, more serious round of the euro crisis.

Desmond Lachman is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts