Italian labor issue shows why eurozone may be doomed

Among the eurozone’s most critical flaws as a construct is that it has tied together countries with very different abilities to improve their labor productivity performance in a single monetary union, in which all member countries share a single currency.

Since its introduction in 1999, weak productivity countries in the euro area can no longer depreciate their currencies as they did before 1999 in order to restore lost international competitiveness.

This might not have been of great concern in recent years at a time of euro weakness, which made the eurozone as a whole more competitive in global markets. However, it now could be of serious concern because from the start of 2017, the euro has been strengthening markedly in the international currency market.

European Labor costs

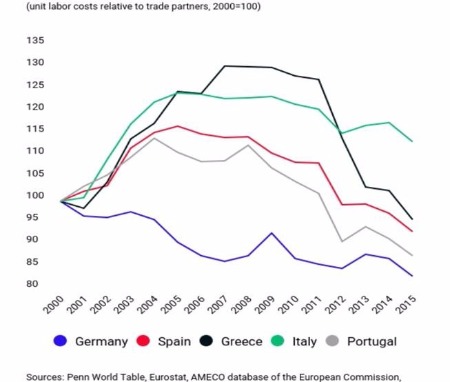

A clear illustration of the euro’s shaky foundations can be derived by comparing unit labor costs in Germany, the eurozone’s largest member country, with those of Italy, the eurozone’s third-largest country.

Since 2000, Germany has consistently demonstrated its ability to improve its labor productivity, as illustrated by a 15-percent cumulative improvement in its unit labor costs. Sadly, the same might not be said of Italy.

Indeed, since 2000, largely due to poor productivity performance, Italy managed to have its unit labor costs rise by a cumulative 15 percent. This implies that over the past 17 years, Italy’s labor market competitiveness with respect to Germany has deteriorated by around a staggering 30 percent.

Over the past few years, Italy’s relative loss of labor market competitiveness has been masked by the very easy monetary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the corresponding weakness in the euro.

However, it now appears that the ECB might soon be scaling back on its expansive asset purchase program and that the euro’s period of weakness might be behind it.

{mosads}Since the start of 2017, the euro has appreciated by 15 percent and looks set to continue appreciating as the eurozone economy keeps growing. This will make it very difficult for Italy to increase its exports and to grow its economy.

Further complicating matters is Italy’s very difficult political landscape. Italy is due to have parliamentary elections early next year that could see a prolonged period of political instability. This is particularly the case given that the election is likely to produce a weak coalition government that could include the populist Five-Star Party.

This makes it highly improbable that Italy will have the political will to undertake much needed economic reforms to improve the country’s poor productivity performance. That in turn is likely to lead to a further loss of international competitiveness with respect to high-productivity eurozone performers, like Germany.

All of this is of the greatest concern considering that Italy desperately needs high economic growth to allow its economy to grow its way out from under its public debt mountain, which currently amounts to around 135 percent of GDP.

Rapid economic growth is also needed to repair its very troubled banking system, where non-performing loans are now as much as 18 percent of its combined balance sheet. This has to raise the basic question as to whether or not it is only a matter of time before the euro area unravels.

This would seem to be especially the case given Italy’s long track record of poor labor productivity performance and its seeming inability to generate meaningful and sustained economic growth.

Desmond Lachman is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts