ARPA-E, the research and development arm of the Energy Department, is looking for “open and audacious ideas” that help to build out “this vision of the energy landscape that doesn’t [yet] exist,” director Evelyn Wang told The Hill.

That funding seeks to answer a question that currently borders on science fiction: how can the U.S. nurture the set of technologies today that will be the core of the American energy system after fossil fuels are no longer part of it?

Over the short-term, the U.S.’s path to greening the grid is straightforward, if fiendishly difficult: install renewables, decrease the use and environmental cost of fossil fuels and build out the electric grid.

But over the long term, the elimination of fossil fuels as a significant power source means three difficult, interlocking problems that ARPA-E is seeking to get out ahead of solving, Wang said.

First, the U.S. will have to find new sources of carbon-free energy to provide electricity, power and heat — which means turning to resources familiar, exotic and as-yet-unheard of.

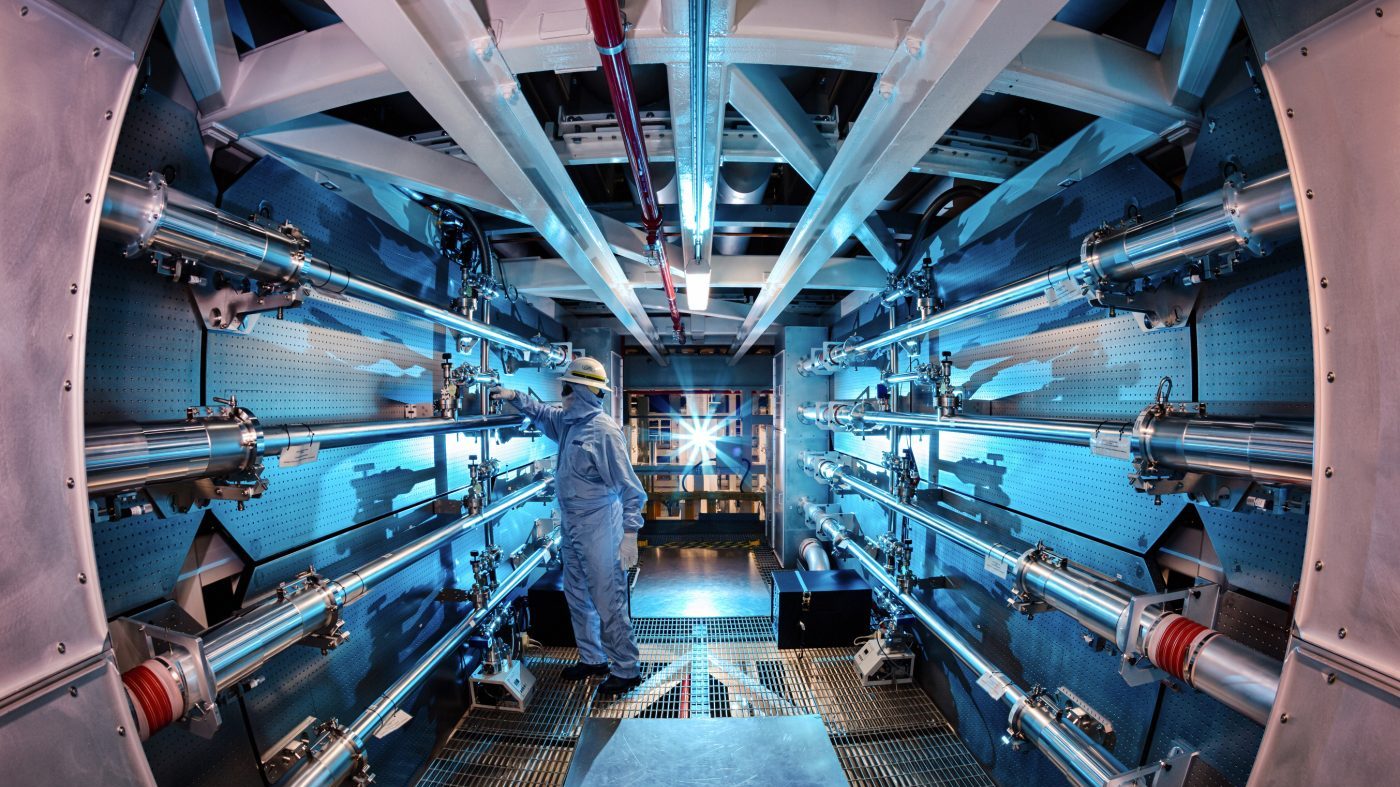

ARPA-E is looking to fund “rapid technologies that help rapid deployment of existing clean primary energy sources, but then also the nascent ones that we want to keep on pushing and that includes like, fusion and geologic hydrogen, which we are just starting to explore — and maybe primary energy sources that we don’t yet know exists,” she said.

The second step will be moving that energy across the country through an “intermodal superhighway” — a means of transitioning energy as needed between electricity, fuel and heat with as little loss as possible.

The U.S. currently has such a system, albeit a highly polluting one: energy moves across the country in the form of coal and fuel cars on railways, tankers and pipelines — which help power the nation’s grid.

In the future, Wang said, power will need to move through an interlocking network of light, electricity and heat. That could look like pipelines moving hydrogen fuels, which would require the gas to be trapped and pressurized on one end and tapped on the other.

Or it could mean regional scale “thermal energy superhighways,” that move heat directly through pipelines insulated with novel materials, or in a medium that retains heat for long enough to allow it to move from place to place. (The problem with transporting heat is “it can be very lossy, because heat diffuses everywhere,” Wang said.)

Anything is on the table, she said, “that doesn’t violate the laws of physics.”

Finally, ARPA-E is spending on projects that help replace the materials — chemicals, fertilizers, plastics — that come from fossil fuels. About 10 percent of primary fossil fuel production goes to provide the structure of materials — which means that currently much of the built world rests on an invisible subsidy provided by the demand for the remaining 90 percent.

The world gets “all these carbon-based products from fossil fuels right now — how do we actually get the products that help us with our daily lives?” Wang asked. “So, in parallel to the energy transition, you have to consider now the carbon transition, where carbon becomes the sustainable building block of the future.”

This could mean large scale use of microbes or algae to bind carbon in usable form — or it could mean that the current oil sector transforms from a source of planet heating fuels to something more like mining: a source of raw material.

In that world, current fuel refineries would be more like “materials factories,” Wang said.

But part of the point of open calls from ARPA-E is that they are deliberately vague: the agency knows that it doesn’t yet know what it doesn’t know.

A similar open call led to an ARPA-E investment that helped stand up Fervo — now a startup which will soon experiment with creating round-the-clock clean power using the Earth’s underground heat at a military base in Nevada.

Fervo’s pitch was how to integrate existing oil drilling technology with emerging imaging and AI tech to “know where to drill and what kinds of subsurface formations” would yield usable heat — and how to pull that heat out.

That’s the kind of new solution to an existing problem ARPA-E is looking for, Wang said.

“What should the future look like, that we don’t have today?” Wang asked. “That’s how we framed this vision.”