GOP faces growing demographic nightmare in West

NORTH LAS VEGAS — When the Mirage Hotel and Casino opened in 1989, it kicked off one of the most significant construction booms in recent history.

Four new mega-casinos opened in quick succession on the Las Vegas Strip, bringing in tens of thousands of new residents to work as card dealers, cocktail servers, security guards and maids.

Among the new arrivals was a family of undocumented Mexican immigrants who found a house in the impoverished bedroom community of North Las Vegas, where their son found a local team to play soccer with.

{mosads}After winning citizenship, that son became the first formerly undocumented immigrant to claim a seat in Nevada’s state legislature.

Today, Rep. Ruben Kihuen’s (D-Nev.) family still lives in North Las Vegas, and his mother still cleans hotel rooms.

“My story’s a very common story,” Kihuen said at a cafe recently, just a block from the field on which his soccer team played.

It’s a deeply personal tale that points to a growing problem for Republicans: Demographic change is slowly, but inevitably, moving Western states to the left.

The political power of Las Vegas is a hint of the GOP’s worst-case scenario: A mega-metropolitan area so dominant, and so Democratic, that it swamps the Republican advantage in increasingly conservative rural areas.

Republicans who have watched Nevada politics in recent years worry their party’s struggles in the Silver State will be a harbinger of things to come as the face of the American electorate changes — especially in other Mountain West states such as Arizona and Colorado.

“The Wild West is slowly becoming an Urbanized West,” said Mike Slanker, a Republican strategist in Las Vegas.

The vast majority of Nevada’s growth has come in Clark County, which has seen its population jump from 48,000 in 1950 to 2.1 million today. Waves of immigrants from Central and South America, Asia, the Midwest and California have flocked to the Las Vegas area.

The challenge for Democrats is that many of those new residents are disproportionately unlikely to turn out to vote, especially in midterm elections.

But if they do show up, the GOP’s nightmare scenario will be realized.

And it could also spread to states with metropolitan areas experiencing significant Hispanic population growth such as Texas, Georgia, North Carolina and Florida.

This is the 11th story in our Changing America series, in which we investigate the demographic and economic trends shaping the nation’s politics. Nevada’s booming growth underscores the two trends working most in Democrats’ favor: the rising power of cities that are acting more reliably liberal, and the expanding influence of Hispanic-Americans who are becoming the nation’s largest minority community.

The population boom has made Vegas an overwhelming force in Nevada politics: When Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid retired in 2016, his hand-picked successor, Catherine Cortez Masto, won Clark County, lost every other county in the state and won the election.

In 2018, Democrats have a chance to put Nevada solidly in the blue column if they can win an open-seat governorship and defeat Sen. Dean Heller (Nev.), who is considered the most vulnerable Senate Republican up for reelection next year.

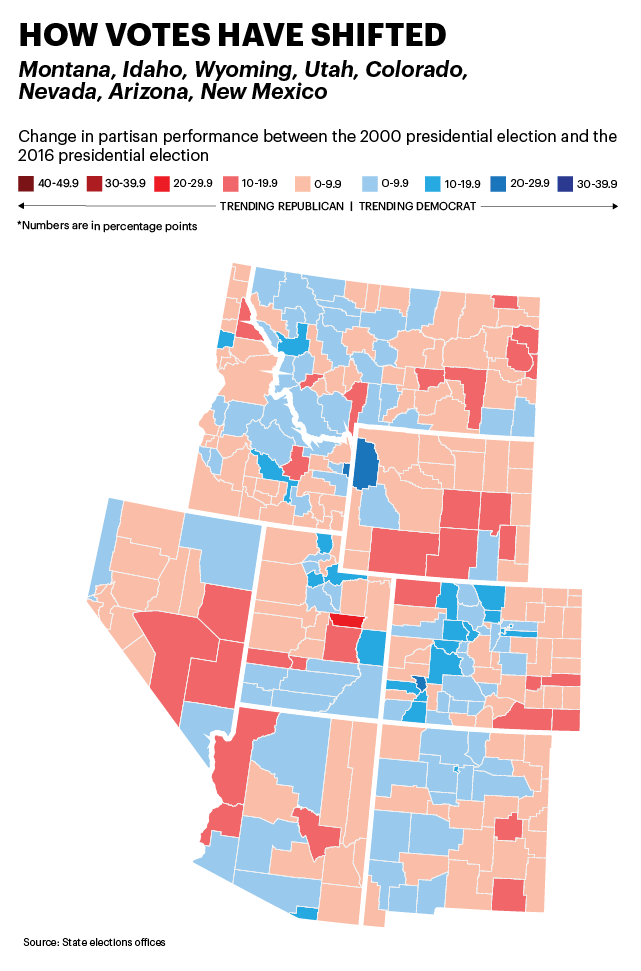

Republicans still control most offices in Mountain West states. In the eight states within the region, stretching from Montana in the north to Arizona and New Mexico in the south, the GOP owns 10 of 16 Senate seats, 19 of 31 House seats and six of eight governorships.

But many of those seats are at stake in the 2018 midterm elections: Republican governors of Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada and New Mexico face term limits, as does the Democratic governor of Colorado. The two most vulnerable Republican senators facing reelection are Heller and Arizona’s Jeff Flake. Democrats are targeting a handful of U.S. House seats in the region.

Most Mountain West states, like Nevada, are dominated by a single fast-growing metropolitan area.

Residents in Clark County account for about 7 in 10 votes in Nevada’s statewide elections. They take in 71 percent of the personal income earned across Nevada; only one county, Honolulu, makes up a bigger share of its state’s economy than does Clark in Nevada, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Clark accounted for 85 percent of Nevada’s population growth in the last five years. Washoe County, home of Reno, accounted for virtually all of the rest.

Next door in Arizona, Phoenix’s Maricopa County represents about three-fifths of the votes cast in a statewide election, and it accounts for 80 percent of the state’s population gains in the last five years. Two of every three dollars earned in the state come from Phoenix.

In Colorado, the six counties that make up the Denver metropolitan area — Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Broomfield, Denver and Jefferson — account for about half of the votes in recent statewide elections. Albuquerque and Santa Fe similarly dominate New Mexico politics. Salt Lake City and its neighbors, Ogden to the north and Provo to the south, make up nearly two-thirds of all votes in Utah.

As the Mountain West’s population becomes more urban, a region once dominated by libertarian conservatives is slowly turning blue. George W. Bush won Nevada and Colorado twice, and New Mexico once.

All three states have voted Democratic in the last three presidential contests. In 2016, Nevada and New Mexico were rare bright spots for the party on an otherwise glum election night.

Arizona has voted Democratic just once since 1952, when it gave Bill Clinton a 46.5 percent plurality in 1996. But it was a target of Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016. President Trump won the state, and Maricopa County, but by smaller margins than any Republican in recent history.

“Arizona, by the time you get to [2020], Democrats will take it seriously,” said David Damore, a political scientist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Damore, who has conducted research into Hispanic voters for the Democratic firm Latino Decisions, said the changing political nature of the Mountain West is being driven not only by new immigrants, but also by Kihuen and other children of those immigrants.

Where the Hispanic immigrant community once segmented itself by country of origin, creating distinctly Mexican or Honduran or Guatemalan populations, the younger generation sees itself as more generally Hispanic and less specifically tied to ancestral homelands.

Those younger Hispanic voters grew up during, and were deeply influenced by, years of debate over reforming the nation’s immigration system. While advisers to Bush understood the importance of reaching out to Hispanic voters — Bush won 44 percent of the Hispanic vote in 2004 — conservatives in Congress blocked his second-term push for immigration reform.

The “immigration [reform debate] has created a pan-Latino identity. You started to see that during the Bush years,” Damore said.

The GOP is still paying for some of the language its party used, during that debate and subsequently. An increasingly conservative primary electorate has only exacerbated the incentive to take a hard line on immigration reform, something Trump capitalized on during the 2016 primaries.

That may play in Republican primaries and in states dominated by white voters, but it hurts in a more diverse state like Nevada, where intemperate comments from candidates have cost the GOP winnable seats. Trump’s comments vilifying immigrants may have been decisive in Nevada, too: Ninety percent of Clinton’s winning margin there in 2016 came from the 80 most Hispanic precincts in Las Vegas, Damore’s analysis found.

“In a [Republican] primary, you’ve almost got to be Trump-like, and then the general comes around and you realize you can’t win that way,” said Peter Guzman, a conservative who heads the Latin Chamber of Commerce Nevada.

Guzman pointed to a second set of immigrants influencing Nevada’s changing political behavior: Californians, mainly blue-collar workers, who come in search of jobs now that the recovery has sent Las Vegas’ economy skyrocketing.

“In the last 15 to 20 years, most of the people who came here came from California,” Guzman said in an interview. “Now they’re voting like they did in California.”

The two most prominent Republicans in Nevada, Gov. Brian Sandoval (R) and Heller, are decidedly not in the Trump camp.

Sandoval was so popular that Democrats did not bother to field a serious challenger when he ran for reelection in 2014. A centrist Republican who supports abortion rights, Sandoval opted to expand Medicare under the Affordable Care Act. In recent weeks, he has become one of the most vocal opponents of the Republican effort to repeal and replace ObamaCare, which would cost his state billions, or cost tens of thousands of his residents their insurance.

Heller, who is close with Sandoval, has spent his career in Congress backing immigration reform and a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Sandoval’s opposition to the Senate healthcare bill has given Heller cover to distance himself from an unpopular bill and an unpopular president who lost his state — though some conservatives in his state have threatened to challenge Heller in next year’s primary.

Stuck in an unenviable position, Heller, who won election with just a 45.9 percent plurality in 2012, is Democrats’ top target for defeat next year.

But ousting an incumbent is no mean feat, and while Heller faces a daunting demographic challenge, Democrats have their own political hurdles to climb: The voters Democrats most need to turn out, those Hispanics in Las Vegas, are disproportionately unlikely to vote.

“It has been a challenge to get these folks not only to assimilate, but getting them to the polls,” Kihuen said of Hispanic voters moving into the state. “We’ve come a long way, but it has not been something that happened from one day to the next.”

That’s a microcosm of the problem Democrats face everywhere: Nationally, almost 65 percent of non-Hispanic white voters turned out to vote in 2016, according to political scientist Michael McDonald at the University of Florida. Nearly 60 percent of non-Hispanic black voters turned out, but only 45 percent of Hispanic registered voters showed up at the polls.

In midterm elections, white voters, and even black voters, have been almost twice as likely to show up as Hispanic voters. That means Democrats have left thousands, maybe tens of thousands, of votes on the table.

“We’re still a relatively low-turnout state, so there’s a huge untapped resource for Democrats,” Damore said.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts