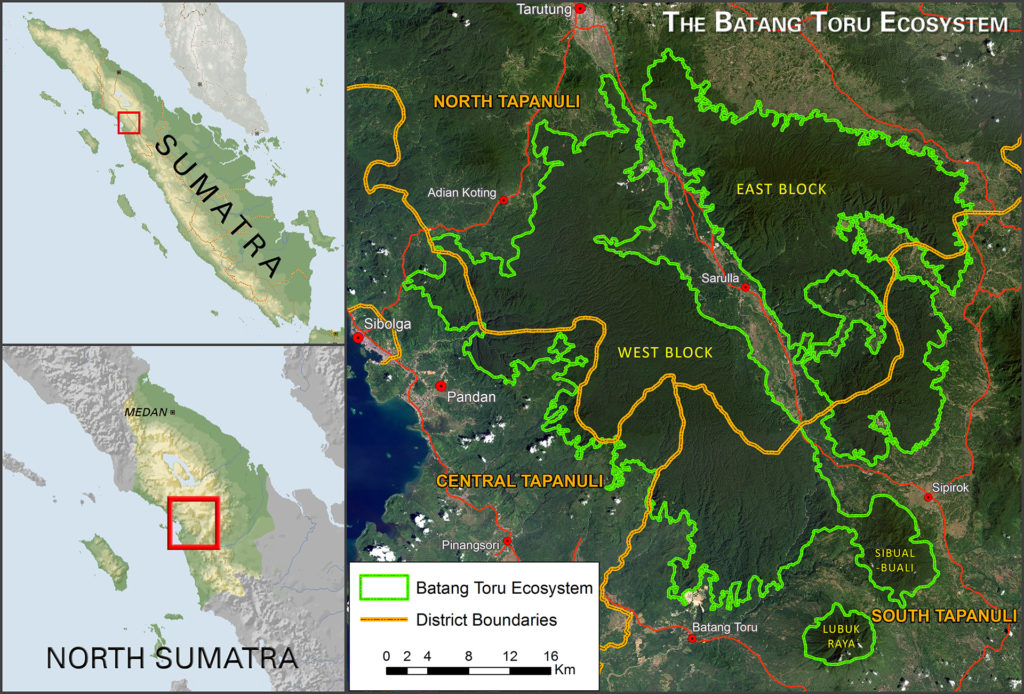

Less than 800 Tapanuli orangutans remain confined to the small mountainous region of Batang Toru in North Sumatra, Indonesia.

Source: https://www.batangtoru.org/

Recognized as a separate species only in 2017, the Tapanuli orangutans suffered a staggering 83 percent decline in just three generations, and retain a mere 2.7 percent of their original habitat occupied 130 years ago.

According to Erik Meijaard, lead author of the recent study and founder of conservation group Borneo Futures, if more than 1 percent of the adult population is extracted — that is killed, translocated or captured — from the wild every year, the species’s extinction is inevitable, which would signal the first great ape extinction in modern times.

America is changing faster than ever! Add Changing America to your Facebook or Twitter feed to stay on top of the news.

By analyzing previously unknown and unpublished historical records, the new research contradicts existing scientific claims with two main arguments: Firstly, the Tapanuli orangutans are driven toward extinction in their original habitat due to unsustainable hunting and habitat fragmentation which continue to plague the species.

Secondly, because they were forced from their natural habitat, they are not adapted to living in highland conditions, and should instead occupy a more diverse range of environments for a better chance of survival, including lowland forests and peatlands.

Hydropower project threatens remaining habitat

Source: https://www.batangtoru.org/

Among the many threats faced by the species, a planned hydroelectric power plant along the Batang Toru River in South Tapanuli Regency came under international scrutiny for encroaching on the last remaining habitat of the Tapanuli orangutans.

Although the company responsible for building the dam, PT. North Sumatra Hydro Energy (PT NSHE) claims that the land occupied by the project — around 122 hectares — is negligible, Meijaard and others have pointed out that the issue is not the size of the power plant, but its location.

READ MORE FROM CHANGING AMERICA

THE CONTROVERSY OVER WILDLIFE KILLING CONTESTS

SURPRISING STUDY FINDS SHARKS ARE KEY TO RESTORING DAMAGED HABITATS, FIGHTING CLIMATE CHANGE

FLORIDA BANS TOILET-INVADING IGUANAS AND 15 OTHER INVASIVE SPECIES

COLORADO HUNTER RECEIVES LIFETIME BAN FOR BEING A DANGEROUS THREAT TO WILDLIFE

IS BACKYARD BIRD-FEEDING GOOD FOR OUR FEATHERED FRIENDS?

The project sits at the intersection of three subpopulations of Tapanuli orangutans which could be permanently separated if the dam is built. According to the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme (SOCP), the western block is considered the only genetically viable population in the long run, so connecting it to the eastern block and two smaller nature reserves are critical to preventing inbreeding and disease, and increasing genetic diversity and thus the survival rate of the species.

Construction for the dam was temporarily suspended in January 2020 because of COVID-19, and as the Bank of China, slated to become one of the main financiers of the project, has seemingly withdrawn funding, the project faces a delay of up to three years.

Meijaard and co-author Serge Wich, co-vice chair of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) primate specialists’ section on great apes, have questioned the scientific validity and objectivity of the environmental impact assessment that was carried out by individuals hired by PT NSHE.

They urge to use the suspension of the project as an opportunity to carry out an independent investigation in collaboration with all stakeholders, including the developer, the government, SOCP and IUCN.

Lack of transparency

PT NSHE could not be reached for an interview, but the IUCN released a fact-checking report in 2020 which refutes in detail claims made by the company on the minimal impact of the hydro project on the Tapanuli orangutans and their surrounding ecosystems, and efforts undertaken to mitigate this impact.

Allegations about widespread crackdown on those who spoke up against the hydro dam abound, although PT NSHE denied these claims. Defamation charges and the dismissal of conservationists on the ground were compounded by the suspicious death of an environmental activist and legal aide who at the time was working on a lawsuit aimed to revoke the environmental permit for the dam.

Many of the conservationists and scientists involved on the ground declined a request for comment on the state of the hydro project or efforts to protect the Tapanuli orangutan, often citing fear of backlash. Reluctance to share information publicly reflects a lack of transparency over the issue, says Wich.

Government officials, including Minister of Environment and Forestry Siti Nurbaya, said that the Tapanuli orangutan is at no risk of extinction, and that the hydropower project will have no detrimental impact on the species’s living conditions.

Other threats faced by the species

Wich also cautions against letting the hydropower project divert efforts from addressing some of the other risks faced by the Tapanuli orangutans. Habitat loss in the area has, over the years, been exacerbated by a variety of extractive activities, including logging, gold and silver mining and geothermal power generation.

SOCP has successfully advocated for a status change in 2014 for 85 percent of the Batang Toru Ecosystem from “production” to “protection forest” which would prohibit any extractive activities. The remaining area, however, is still home to the highest density — 10 percent — of the remaining Tapanuli orangutan population.

Unsustainable hunting and weak law enforcement

In addition, according to Meijaard, orangutan conservationists tend to focus on deforestation and habitat loss, when in reality, the biggest risk is the unsustainable hunting and capture of the species that have been a regular practice for centuries based on the historical records examined in his latest study.

Although orangutans are protected by both national laws and international conventions, “there appears to be a lack of political will to convict people who illegally poach, harm or own orangutans, compared to other wildlife crime,” says Julie Sherman, executive director at nonprofit Wildlife Impact.

Citing a scientific study, Sherman contrasts the prosecution rate for the illegal poaching and trade of tigers at 90 percent compared to only 0.1 percent for orangutans.

Translocation should remain last resort

Based on figures shared by Meijaard, approximately $80 million is spent on orangutan conservation every year, yet the population numbers of all three orangutan species — the Bornean, the Sumatran and the Tapanuli orangutans — continue to dwindle.

The current focus on orangutan translocation, rehabilitation and reintroduction to the wild is very expensive, and there is limited data available on the welfare or survival rate of the orangutans due to limited post-translocation monitoring, says Meijaard.

Once they are reintroduced into the wild, it’s challenging to track the orangutans remotely because there is no technology available yet, such as chips implanted into the released animals, that’s both reliable and safe for the orangutans, explains Ian Singleton, director of SOCP.

SOCP, a partnership between the PanEco Foundation, the Foundation for Sustainable Ecosystem (YEL) and the Directorate General of Nature Resources and Ecosystem Conservation, operates the only orangutan rehabilitation center in the area.

“Whilst [translocation] may sometimes be in the best interests of the individual orangutans concerned, namely getting them out of a situation in which they are likely to die or be killed, it is not really a sustainable solution to the problem of human-orangutan conflicts, nor is it likely to make much of an impact on the long term conservation prospects for the species, at least at the present time,” adds Singleton.

Translocation does not negate the need to address the wider issues of habitat loss and weak law enforcement, says Panut Hadisiswoyo, founder of the nonprofit Orangutan Information Centre (OIC).

The rescue of a Tapanuli orangutan by OIC, YEL and government conservation agency BBKSDA Sumut. Photo credit: BBKSDA Sumut and OIC

While critics warn that translocation is often considered an easy fallback option because the government has made it so easy to report a trespassing orangutan, Hadisiswoyo believes that it’s best to be immediately alerted to a potential human-orangutan conflict so it can be addressed without loss of life.

Prevention and education

Both the SOCP and the OIC place great emphasis on preventative measures to reduce the need for translocation, including the education of local communities on the value of safeguarding orangutans and their ecosystems.

“A coordinated approach is desirable … to tackle not only the drivers of habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation, but also community issues that often result in the killing of orangutans in conflict situations,” says Singleton.

Initiatives include building buffer zones of plants to prevent orangutans from crossing over to villages, or conflict mitigation training. The OIC, for example, is teaching locals how to make and use noise-making tools such as bamboo cannons to scare away crop-raiding orangutans without injuring or killing them.

Primatologist Wanda Kuswanda argues in his recent study for the need to offer noncash support to local communities, including seeds for plants that cannot be consumed by orangutans such as coffee, cocoa or snake fruit. He also recommends developing orangutan ecotourism ventures to demonstrate the economic value of protecting the species.

COVID-19 exacerbates extinction risk

The COVID-19 pandemic has, however, made conservation efforts imminently more challenging.

Although there is limited information on the health impact of COVID-19 on great apes and there are no known cases of infected orangutans, conservationists cannot risk even a small chance of infection for a species that is so close to extinction already.

Although rescue, translocation and rehabilitation efforts continue, no orangutans have been released into the wild by SOCP since March 2020, and most research studies focused on wild orangutans have been suspended in the past 12 months to mitigate contagion risk.

SOCP’s captive orangutan facilities are operating with strict precautionary measures which have incurred considerable costs at a time when conservation organizations grapple with dwindling funds from both donors or income-generating activities such as tourism.

In addition, based on satellite imagery and other sources, Singleton warns that illegal activities have increased in the forests, as have orangutan killings. Tolerance for the crop-raiding great ape is decreasing as villagers struggle to earn a livelihood amidst the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Despite the grim situation, conservationists and scientists such as Wich or Hadisiswoyo believe that there is still a chance to save the Tapanuli orangutans from extinction, but only if a robust action plan is put in place. Efforts need to focus on protecting their remaining habitat, mitigating human-orangutan conflict without having to translocate the animals, and the improved enforcement of wildlife protection laws.

This story was developed as part of the author’s participation in the “Reporting on climate change and energy transition” training and mentorship program organized by the Thomson Reuters Foundation and the European Climate Foundation.

READ MORE FROM CHANGING AMERICA

BIDEN PAUSES NEW OIL AND GAS LEASING ON PUBLIC LANDS AND WATERS

NEW FISHING PROTECTIONS SPELL WIN FOR MAINE’S PUFFIN POPULATION

WILDLIFE GROUPS CHALLENGE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION ON GRAY WOLF DELISTING

THERE’S AT LEAST ONE GROUP 2020 WAS GOOD FOR: GREAT WHITE SHARKS

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Changing america