The pervasive myth of an immigration crisis

We’ve crunched the numbers. The immigration “crisis” you heard about over the summer does not live up to the cable news hype.

It is true that apprehensions of unaccompanied children and families crossing the border spiked over the summer in south Texas, reaching a tipping point for effective detainment and immigration processing. This phenomenon, however, has since subsided, and more importantly, it is not an indicator of a broader “illegal immigration crisis” as touted in the media. In fact, the border line is today under greater operational control than ever before, and the data indicate that immigration has decreased significantly along the U.S.-Mexico border over the past decade. Moreover, the undocumented population living in the United States is today lower than it was just a few years ago.

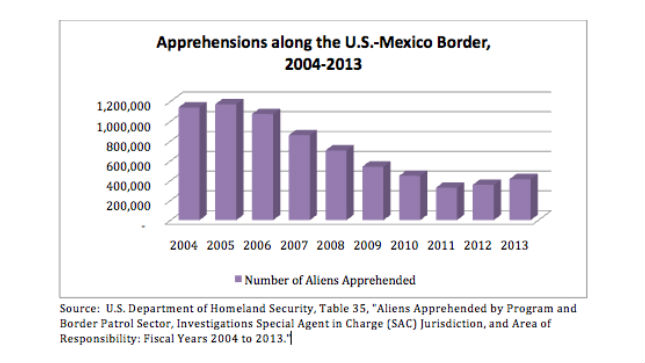

Fewer people are crossing the border

Between 2004 and 2014, apprehensions along the U.S.-Mexico border fell by nearly two-thirds. Much of this decline can be attributed to the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent weakening of the U.S. job market, as well as improved economic conditions in Mexico. In addition, living and working inside the United States without papers has become nearly impossible. That has made many undocumented migrants simply self-deport. The Obama administration too has deported some 2.5 million migrants, further reducing the undocumented population. The number of annual deportations may in fact match today the number of apprehensions of undocumented crossers at the border, netting a migration of around zero.

{mosads}Much of the drop-off in the gross numbers can indeed be attributed to a dramatic decrease in apprehensions of Mexicans, even though migration from Central America’s Northern Triangle (Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador) has not eased. This is largely due to continued violence and lack of economic opportunities in these countries.

Operational control of the border has increased

A dramatic increase in the operational control of the border in recent years provides further evidence against an at-large crisis.

Since 2004, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection budget has more than doubled to $12.9 billion, and Border Patrol staff on the Southwest border has increased in number from 9,506 to 18,611. The government has also invested heavily in surveillance technology and physical barriers. Under the Obama administration, drones have been added to this arsenal of border control.

Academic literature on the subject demonstrates that an increase in patrol agents lowers the likelihood that immigrants will succeed in crossing the border, thus serving as a deterrent to subsequent immigrants. More agents plus better surveillance also increases the likelihood that border crossers are caught.

With this in mind, looking at the apprehensions in the chart below, it’s not hard to assume that the proportion of apprehensions relative to the total number of border crossers in 2004 was much lower than it was in 2013. There’s no way to know these statistics for sure, but hypothetically, if the U.S. government was apprehending 60 percent — 1.14 million — of the total border crossers in 2004, with a more effective operational control of the border it may now be apprehending upwards of 85 to 90 percent — or 414,397 — in 2013, thanks to personnel and technology upgrades. That would imply that the total number of people attempting to cross without documents has decreased even more dramatically than the chart above would indicate.

But what about those kids in south Texas?

Unaccompanied children crossing the border — especially from the Northern Triangle — have indeed surged from 38,805 in fiscal year 2013 to 67,339 in 2014, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. For the same period, family unit apprehensions, defined as a parent traveling with a child, are up from 14,855 to 68,445.

The truth is that since 2011, more and more minors and families from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador have decided to brave the journey to the United States. The crisis you heard about over the summer reached a tipping point last year when detainment facilities along the border, designed to confine and house adults, became overwhelmed with minors who, under U.S. and international law, couldn’t merely be deported home upon capture.

Push and pull factors shed light on migrants’ motivations and reasons for the uptick. Gang-related violence and economic malaise in each of these countries have led to increased migration to the United States among minors and adults alike. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program also stirred false rumors of legal status for minors who make it to U.S. soil. The government rightly defined the influx as a humanitarian crisis, pointing to both the dangerous situation in Central America pushing these kids northward as well as the rather bleak conditions at U.S. detainment facilities not designed to house large numbers of children. Although strife continues in Central America, U.S. policies aimed at stemming the flows of these groups have reduced current flows to “pre-crisis” levels: more infrastructure was put in place to detain, process and deport children and families, and the U.S. launched a public awareness campaign in the Northern Triangle to reverse misinformation about DACA. Mexico also began cracking down on migrant flows along its border with Guatemala.

Beyond this very specific demographic, though, there’s really no cause for concern. It’s true that children and family units were a serious concern for border management for a few months, but it was managed, and deeming it an outright crisis completely jumps the gun. What about the allegedly porous, insecure border that Congress uses as a scapegoat for delaying immigration reform? That’s far from the truth. Overall apprehensions are way down; border security is up; the undocumented population within our borders is down.

It’s time that politicians and the media set their border paranoia aside and focus on real immigration reform. The numbers show that we have a window of opportunity to deal with this once and for all, instead of reaching to the bottom of the barrel to find an inexistent crisis as a reason not to fix the immigration system.

Payan, Ph.D., is director of the Mexico Center at Rice University’s Baker Institute. He is the editor of Undecided Nation: Political Gridlock and the Immigration Crisis. McNally is a research analyst for the Mexico Center. This article is based on a paper by Payan and William C. Gruben and published by the Baker Institute.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts