We must not turn recession fears into self-fulfilling prophecies

What does the Fed know that we don’t? That is the question that I have been asked the most over the past week. The Fed’s paradigm shift to a significantly more dovish stance has left everyone wondering what type of recession monster is lurking under the economy’s bed.

With the yield curve — the spread between the yield on 10-year Treasuries and the yield on 3-month Treasury bills — inverting for the first time since the financial crisis, the dreaded “R-word” is back on everyone’s lips: When are we due for a recession?

To answer that question, let’s take a step back from the wild market ride of the last several days. What has changed, what has not, and how should we fear the next recession?

The Department of Commerce’s GDP report showed the U.S. economy reaching an inflection point at the end of last year. Fourth quarter (Q4) real GDP growth was estimated at 2.2 percent, representing a substantial slowdown from 4.2 percent and 3.4 percent growth in Q2 and Q3.

Consumer spending advanced a downwardly revised 2.5 percent in Q4 after growing 3.5 percent in Q3. Business investment picked up in Q4 to a firm 5.4-percent rate following 2.5-percent growth in Q3, and residential investment remained depressed, falling for the fourth consecutive quarter, down 3.5 percent.

As such, while the economy posted its strongest performance in three years in 2018, rising 2.9 percent on the back of a large fiscal boost, momentum is no longer accelerating.

In fact, Oxford Economics foresees real GDP growth slowing from 3 percent year-over-year at the end of 2018 to less than 2 percent year-over-year by early 2020.

Dissipating fiscal stimulus, mildly tighter financial conditions, slower global growth and softening private-sector confidence will all contribute to the slowdown. However, it is important to remember that shifting momentum around inflection points don’t necessarily translate into recessions.

What slower economic momentum does lead to is downward pressure on inflation. As activity moderates, resource utilization tends to cool, and input costs and prices rise less rapidly. This, in turn, can lead to a gradual erosion of inflation expectations, which tends to feed back into lower inflation.

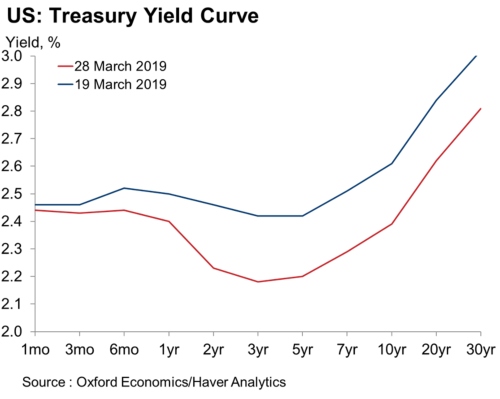

Viewed in this context of gradually eroding economic growth and moderate inflation, at home and abroad, a flatter yield curve becomes the “new normal.” But, the yield curve did not just flatten last week, it inverted in the wake of the March Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting.

And, we know that inversions remain key leading indicators of recessions, with long — nearly two years on average since the 1980s — and variable lags — ranging from 10 months to three years.

So, should we panic? No. Instead, we should make a concerted effort to avoid succumbing to the most important domestic risk — the recession bias, which could in turn lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Indeed, while U.S. fundamentals remain generally solid, a private-sector retrenchment in the face of policy uncertainty and global central bank dovishness is an important risk to monitor.

Whether it means to or not, the Fed’s extremely dovish pivot is partially feeding this recession bias. Its paradigm shift following the March FOMC meeting — which revealed that Fed policymakers don’t expect anymore rate hikes in 2019 and will end their balance sheet normalization by October — surprised investors and led the to a sharp decline in long-term yields.

With global central banks following, or expected to follow the Fed’s dovish lead, and global economic data titled to the downside, safe-haven and yield-reaching flows into Treasuries pushed yields even lower.

In turn, the sharp downward movement in long-term yields has led to a technical repositioning of some portfolios that further exacerbated the decline in yields.

Once some of these technical forces unwind, and assuming economic data firm past the first quarter soft patch, it wouldn’t be surprising to see a moderate reversal in long-term yields. This could eventually lead to a yield curve “reversion” (with a positive spread reappearing between long- and short-term Treasury securities).

In short, while it appears we should get used to the new normal of modest growth, muted inflation, a dovish Fed and a flat yield curve, we should be careful not to talk ourselves into a recession. The wise words of Franklin D. Roosevelt ring true in today’s environment: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself”!

Gregory Daco is the chief U.S. economist for Oxford Economics. Follow him on Twitter: @GregDaco.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts