Slowly but surely, gains from AI innovation are coming

Each day we read about amazing technology breakthroughs, particularly when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI). But if AI is so great, why are these breathtaking technological achievements not matched with soaring productivity and economic growth? Or, to paraphrase an old jibe: If the economy is so smart, why aren’t we all rich?

After all, we live among astonishing examples of potentially transformative new technologies that could greatly increase productivity and economic welfare. As noted in the 2014 book, “The Second Machine Age,” leaps in AI, machine learning and, more recently in areas such as image recognition, abound. Investments in AI-related companies surged to over $5 billion in 2016.

{mosads}At the same time, measured productivity growth over the past decade has slowed to half of its level in the decade preceding the slowdown. The sluggishness is also widespread, occurring throughout the U.S., the U.K. and other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations, among others.

In the U.S., the Congressional Budget Office reduced its 10-year forecast for average annual labor productivity growth from 1.8 percent in 2016 to 1.5 percent in 2017. Although modest, that drop implies GDP will be considerably smaller 10 years from now than it would be in a more optimistic scenario — a difference equivalent to almost $600 billion in 2017.

When we studied the topic in depth, however, we drew a surprising and significant conclusion: There is no inherent inconsistency between forward-looking technological optimism and backward-looking disappointment. Both can simultaneously exist.

The nature of transformational technology

Indeed, there are good conceptual reasons to expect them to simultaneously exist when the economy undergoes the kind of restructuring associated with transformative technologies. Corporate wealth and the measurers of historical economic performance show the greatest disagreement precisely during times of technological change. Our evidence suggests that the economy is in such a period now. Economic value lags technological advances.

To be clear, we are optimistic about the ultimate productivity growth fueled by AI and complementary technologies. The real issue is it that it takes time to implement changes in processes, skills and organizational structure to fully harness AI’s potential as a general-purpose technology (GPT). Previous GPTs include the steam engine, electricity, the internal combustion engine and computers.

In other words, as important as specific applications of AI may be, the broader economic effects of AI, machine learning and associated new technologies stem from their characteristics as GPTs: They are pervasive, improved over time and able to spawn complementary innovations.

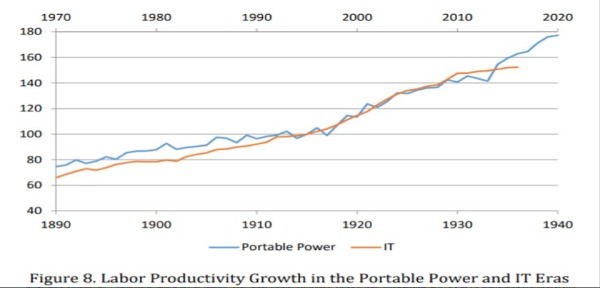

Besides their direct impact, each GPT also increases productivity by spurring important complementary innovations. And as with other transformative technologies in the past, such as the “portable power” of electricity and steam engines and IT, the timeframe for AI adoption can take many years or even decades and involve waves of productivity slowdowns and accelerations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Labor Productivity Growth in the Portable Power and IT Eras

Note: The portable power series shows U.S. labor productivity levels from 1890-1940, normalized to a value of 100 in 1915. The IT series shows U.S. labor productivity levels from 1970-2016, normalized to a value of 100 in 1995.

Why the lag?

Rodney Brooks, professor of robotics (emeritus) at MIT and chairman of Rethink Robotics, recently wrote a blog post with some terrific insights and examples of how technology implementation takes time.

He notes that people often “underestimate how long new technologies will take to be adopted after proof-of-concept demonstrations.” In the case of AI, he says, this is leading to great disappointment “about how the good future we thought we were promised is taking much longer to be deployed than we had ever imagined.”

In fact, this is how transformative technologies typically get infused in the mainstream. Having ideas is easy, as Brooks notes, “turning them into reality is hard.” Deploying them at scale is even harder.

There are plenty of optimists as well as pessimists when it comes to technology and growth forecasts. The optimists tend to be technologists and venture capitalists, and many are clustered in technology hubs. The pessimists tend to be economists, sociologists, statisticians and government officials. Many of them are clustered in state and national capitals.

There is much less interaction between the two groups than within them, and it often seems as though they are talking past each other. In an important a sense, they are.

Nevertheless, these two perspectives are not contradictory. In fact, in many ways, they are consistent and symptomatic of an economy in transition. The demonstrated breakthroughs of AI technologies are not yet affecting much of the economy, but they portend bigger implications as they diffuse.

Realizing the benefits of AI is not automatic, nor is it fast. It will require great effort and entrepreneurship to develop the needed complements and adaptability at the individual, organizational and societal levels. Theory predicts that the winners will be those with the lowest adjustment costs and those who put the right complements in place.

Technologies with widespread potential require major adjustments to business processes, capital infrastructure and job design to realize their full economic value. Understanding history, gaining perspective and using the right roadmap will help AI value creation arrive sooner rather than later.

The good news is that we already see early signs of the coming productivity resurgence, and this one could be as big or bigger than any of the ones we saw in the past.

Erik Brynjolfsson is the Schussel Family professor at the MIT Sloan School, the director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy. Daniel Rock is a Ph.D. candidate at MIT Sloan and researcher at the Initiative on the Digital Economy. Chad Syverson is the J. Baum Harris professor of economics at the University of Chicago, Booth School of Business. The full working paper on this subject can be found here.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts