Democrats and Republicans alike are weighing whether the November midterm elections will turn into a blue wave that acts as a referendum on President Trump, or whether voters will make only modest adjustments to the levers of power in Washington because of a strong economy.

No one is popping any champagne just yet: Public and private polls show a deeply unsettled landscape, one that could break hard for Democrats — or even add to the Republican majority in the Senate.

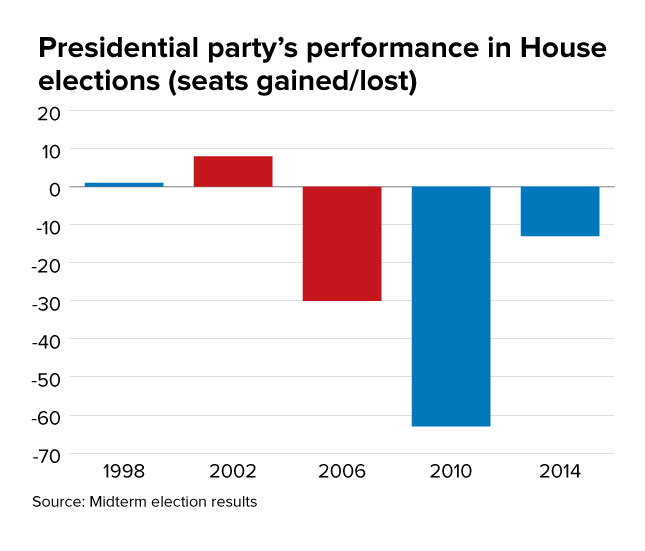

Democrats have an advantage, though not one of historic proportions, based on the usual midterm metrics, including the mere fact they do not hold the White House — which is historically a disadvantage for the party that holds it. But economic indicators, a less reliable metric by which to forecast election results, show some underlying strengths for the GOP.

“Everything politics has taught us in the last four decades suggests you want to be the party out of the White House in a midterm when the president’s net approval is as low as it is today,” said Bruce Mehlman, a Republican lobbyist who closely tracks electoral trends.

“However, those same historical lessons were crystal clear that Hillary Clinton was going to win the White House.”

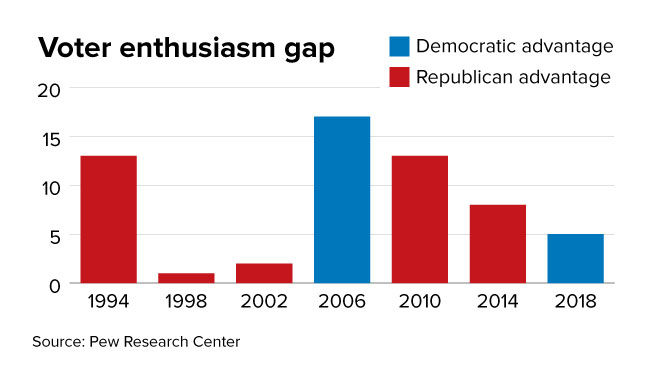

But their edge is not as significant as the winning party’s advantage in the last two major wave elections, in 2010 and 2006. Eight years ago, Republicans held a 15-point enthusiasm edge, and they picked up 63 Democratic-held seats in former President Obama’s first midterm election.

Four years before that, Democrats had a 32-point enthusiasm gap, and the party picked up 30 seats.

“Democrats are angry, and that’s not changing in the next 100 days,” said Ron Klain, a Democratic strategist and former chief of staff to Vice Presidents Joe Biden and Al Gore. “The unknown is whether that anger turns into a huge turnout.”

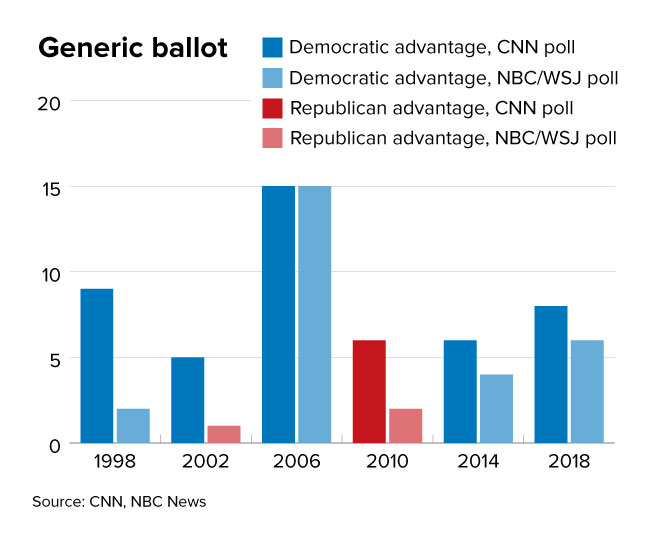

Voters also give Democrats an advantage on the generic ballot question, a common gauge pollsters use to determine which side has an edge in the 435 House races across the country.

That gap has hovered in the 6- to 10-point range in recent weeks. But Democratic voters tend to live in more concentrated areas and the party typically needs a more significant advantage in the generic ballot number than do Republicans, whose voters are spread through more exurban and rural districts.

Democrats need a higher share of the midterm vote to win a majority of seats, in other words, than do Republicans.

In 2014, when Democrats led the generic ballot in both

CNN and

NBC/Wall Street Journal surveys by only slim margins, Republicans ended up winning 13 Democratic-held seats. The last time Democrats gained significantly, in 2006, the party held a 15-point advantage in both surveys.

By contrast, Republicans enjoyed a generic ballot advantage of between two and six points in late October 2010, according to CNN and NBC/Wall Street Journal polls, but that narrow edge still resulted in the 63-seat gain.

“With the generic ballot running about D+6-7, it’s a challenging environment, but not insurmountable,” Brian O. Walsh, who runs a Republican umbrella organization close to the White House, said in an email. “The battlefield will continue to be run through Republican-leaning areas, which will be an asset.”

Trump’s approval rating may matter most of all. Today, his approval rating sits at between 38 percent and 45 percent, according to reputable surveys. That is lower than Obama’s in 2010, when Democrats lost so many seats, but higher than George W. Bush’s in 2006, when Democrats made big gains.

Mehlman said big midterm swings tend to happen when the opposition party is most angry at the sitting president, something he called the “resistance gap.” Trump’s approval rating is just 9 percent among Democrats,

according to Gallup — marginally worse than Obama’s ranking among Republicans in 2010, and marginally better than Bush’s among Democrats in 2006.

“Democrats are very united in their disapproval of Trump,” said Mike Noble, a Republican strategist and pollster in Arizona. “It’s a toxic environment to have an ‘R’ next to your name on the ballot.”

In the last two midterm elections when a president had relatively strong ratings among the other party’s voters — Bush in 2002, and Bill Clinton in 1998, both of whom had approval ratings in the mid-30s among the other side’s voters — the president’s party actually gained seats.

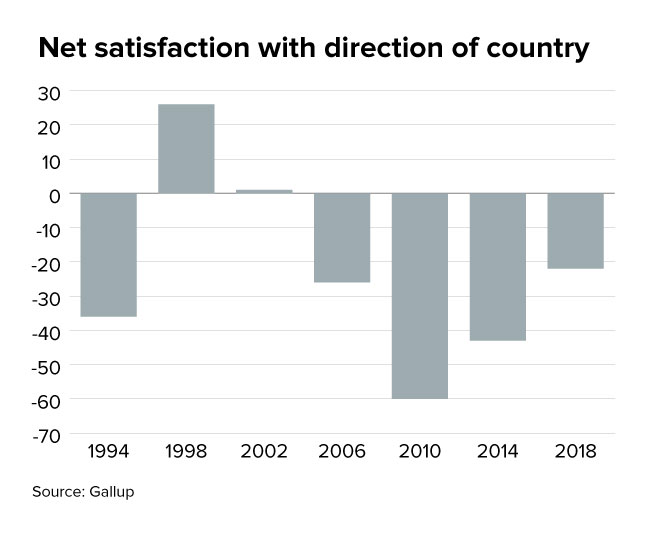

Republicans have pinned their hopes on the fact that more voters are feeling optimistic about the direction of the country than in recent years.

Today, 38 percent of Americans tell

Gallup pollsters they are satisfied with the direction of the country, while 60 percent are dissatisfied. That 22-point gap is smaller than it was in the 2010 and 2014 midterms in which the opposition party made big gains. It is relatively close to the 26-point gap that existed in 2006.

Some Republicans expressed frustration that the White House — and Trump specifically — have been unable to exploit a booming economy and low unemployment rates for political gain.

“The economy and tax reform isn’t an abstract issue like Russia,” said Ryan Williams, a New Hampshire Republican operative who advised Mitt Romney. “I wish the president would talk every day about the economy and tax reform instead of other things he talks about. It distracts from the success story.”

In the last two midterms in which more voters said the country was headed in the right direction than those who said it was off on the wrong track, in 2002 and 1998, the president’s party made gains, even though the unemployment rate was higher than it is today.

Both Democrats and Republicans say the confusing national poll numbers do not tell the full story, and that polls in specific districts tell a more nuanced tale.

In all three cases, the vast majority of competitive seats are currently held by Republicans.

Democrats feel they have an advantage, pointing to the record-breaking number of candidates they have recruited, and to fundraising numbers that continue to impress.

“We had a nail-biter going into the Virginia gubernatorial elections, and we picked up 15 seats [in the House of Delegates] in a Republican-gerrymandered map,” said Jessica Post, who runs the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee. “We have more Democrats running than ever, which means we’ll be able to concentrate resources on key seats.”

Others point to Democratic performance in special elections and primary elections this year.

“For all the ups and downs of polling, the reality is Democrats around the country continue to over-perform, often significantly, in special elections. Moreover, we’ve seen stronger than average turnout in primaries,” said Steve Schale, a Florida-based Democratic consultant.

With three months to go, and billions to be spent prosecuting cases for and against candidates, the public metrics add up to a Democratic advantage of relatively minor proportions. But the fact that Democratic candidates are polling so close to their Republican rivals even this far out scares the GOP.

And Democrats don’t even need an above-average year to win back the House: In midterm elections dating back to 1948, the party that does not control the White House has picked up an average of 36 seats when the president’s approval rating is below 50 percent.

Democrats need to win just 25 seats — including a vacant seat they will almost certainly win — to reclaim control.

“Democrats may not be ahead right now in enough races to win” the House, said Tom Davis, a former chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee. “The Democrats aren’t winning, but they’ve moved these things to single-digit races.”

— Lisa Hagen contributed to this report.

Copyright 2023 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. Regular the hill posts